The Untold History of the Biden Family

At one party, Sheene III was introduced to a stunt pilot named Ken Tyler, who was good friends with both Sheene, Jr., and Biden, Sr. “He was a character,” Sheene III recalled. Tyler, a Canadian Royal Air Force instructor during the Second World War, had been court-martialled for reckless flying. He ran a crop-dusting service that operated out of Fitzmaurice Field, an airstrip on Long Island, and Sheene, Jr., and Biden, Sr., went into business with him. (According to Cramer, they received some financial help from Sheene, Sr., who, like his son, was dodging bills from the government.) In newspaper articles, Biden, Sr., is described alternately as Tyler Flight Service’s general manager and as its vice-president; an airport directory lists him as the manager of Fitzmaurice Field. At the New York Aviation Show, Biden, Sr., announced that Tyler Flight Service handled more contracts for mosquito control than any other aviation company in the country did.

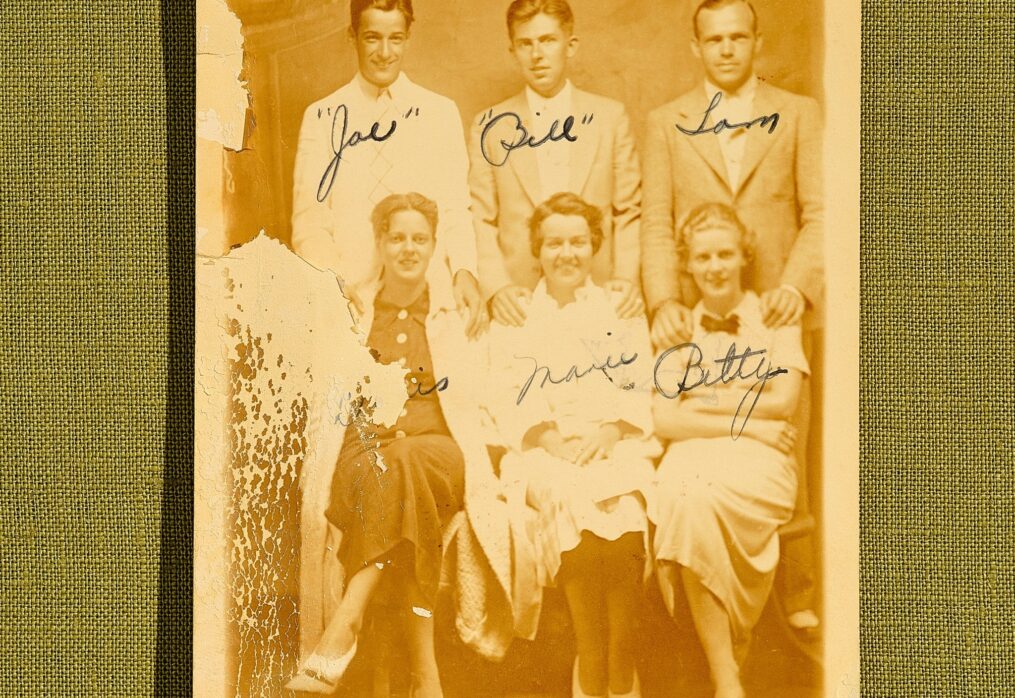

In the fall of 1946, the Biden family moved to a two-story house in Garden City, close to Old Westbury. Jean began to sour on the family’s life in Long Island. According to Cramer, she had been opposed to the crop-dusting business, and she resented Sheene, Jr., for “drinking the company dry” while Biden, Sr., “humped all over the Island, drumming the farmers for jobs.” Jimmy said that his mother was worried about the influence that Sheene, Jr., had on his father: “She thought that the Sheenes would draw out every negative impulse that Dad had.” For many years, Sheene, Jr., had been cheating on his wife, Marie, a close friend of Jean’s. Marie finally left him, taking the kids with her, and in the summer of 1947 Sheene, Jr., sold the Old Westbury estate. Then he temporarily moved in with his cousin.

One evening, as a drunken prank, Sheene, Jr., set off a fire alarm near the Bidens’ home, causing a commotion. Newsday published an article about the incident, which described Sheene, Jr., as “the owner of an airplane or two, a yacht and sundry other playthings,” and gave the Bidens’ address as his residence. Later, Sheene, Jr., told his son that Biden, Sr., had been part of the prank. “When they were together, they were drinking all the time,” Sheene III said. “Jean was probably worried that her husband would end up in jail.” (According to Cramer, Jean went to live with her family in Scranton during this period.)

The crop-dusting business was short-lived. There are varying accounts of what led to its demise: Sheene III said that his father bought an airport in Buffalo, where planes were grounded in a snowstorm, preventing the company from fulfilling its contracts; Sheene III’s stepsister said she’d heard that a drought killed all the crops. Regardless, the Bidens were left with nothing. They sold the house in Garden City, and had no option but to move in with Jean’s family. “By the time I was ready to start school,” Biden wrote in his memoir, “we were back in Scranton—and broke.”

It was a humiliating arrangement for Biden, Sr. “The Finnegan boys used to be pretty hard on him when he was making money, but they didn’t let up when he’d lost it,” Biden wrote. And yet there may have been another reason that Biden, Sr., was so uncomfortable in the Finnegans’ home. In May, 1944, the month that the National War Labor Board went after the Sheenes, Jean’s brother Ambrose Finnegan, Jr., a second lieutenant in the Army Air Force, died in a plane crash in the Bismarck Sea, en route to a village that the Allies had seized from Japan. As the Finnegan side of the family made the ultimate sacrifice, the Biden side was making money from a business that was later called “an unstabilizing influence in one of our country’s most vital war industries.”

Biden, Sr., struggled to find work in Scranton. His brother suggested that he look for a job in Wilmington, a place that they knew well. Biden, Sr., took his advice, and got work cleaning boilers for a heating-and-cooling company. To make extra money, he worked at a weekend farmers’ market selling pennants and other knickknacks. This was hard for him to stomach—a few years earlier, he had been running an entire division of a war-contracting company, with many employees answering to him. But, even though it was a meagre living, the Bidens no longer had to depend on the Sheenes. In a story that Biden later recounted, one day Jean visited the farmers’ market and told her husband, “I’ve never been more proud of you.”

Not that her husband had disavowed the Sheenes. Even though Jean clearly detested Sheene, Jr., in November of 1953, she and Biden, Sr., named their fourth child in part after him. “I didn’t know Uncle Bill very well, but they gave me his name for my middle name—I’m Francis William Biden,” Frank said. “That’s how close my father was to Bill Sheene.”

Biden, Sr., eventually got a job at a car dealership, and the family moved to Mayfield, a suburb of Wilmington. “I always had a sense my dad didn’t quite fit in Mayfield,” Biden wrote in his memoir. At the dealership, Biden, Sr., was the only employee who wore a suit, a silk tie, and a pocket square—folded to four crisp points. Slowly, his children learned more about his past. “We each had our individual journey to understanding our father,” Frank said.

Of the four siblings, Jimmy knew the most about his father; he asked more questions than the others. One day, he said, when he was a boy, his father drove him to a small airport near Wilmington, pointed to a Piper Cub airplane on the tarmac, and told his son to climb into the passenger seat. To Jimmy’s surprise, his father took the controls, and soon they were airborne. After circling the family’s house in Mayfield, Biden, Sr., landed the plane. “This is between me and you,” Jimmy recalled his father saying. “Never tell anyone about this.”

Frank said that his epiphany about his father’s “background as a patrician” came later. For years, a picture of a horse had hung behind Biden, Sr.,’s recliner. One day, Frank asked about it, and his father replied, “That’s Obe.” Biden, Sr., proceeded to tell him about the horse—a jumper named Obadiah—which he had kept in the stables of his cousin’s estate in Old Westbury.

Sometimes Biden, Sr., would take his family on drives through wealthier neighborhoods, and he seemed to admire the estates they passed. “He felt that we should have been in there, and that what he was doing was something less than he wanted to do for us,” Jimmy said. “We never felt poor,” Jimmy went on. “We never felt like we were deprived.” And yet their father seemed ashamed of their comfortable middle-class existence. Later, when Biden became a senator, his father insisted on leaving the car dealership. “This is an embarrassment,” Jimmy recalled Biden, Sr., saying. “I can’t be in the car business.” He became a real-estate broker.

As Biden, Sr., tried to adjust to a middle-class life style, the Sheenes spent the late nineteen-forties and early fifties trying to restore their fortune. After the war, Briscoe, on the other hand, still had his estate, a chauffeur, and a housekeeper. (Years later, he would brag about how he had outsmarted the I.R.S. by buying his estate in his mother’s name.) The Sheenes sued Briscoe, alleging that he had siphoned money off their partnership. “He is the only one who made out like a bandit,” Sheene III told me. But Briscoe and his wife, Marie Gaffney, failed to show up in court. The local sheriff visited their estate and found Briscoe lying down, “inebriated.” A bedroom was locked from the inside, and when the sheriff forced it open he found Gaffney, who had been dead for about a week. According to the medical examiner, her body was “so decomposed that it was impossible to determine an anatomical cause of death.” Afterward, Briscoe filed a motion to dismiss the Sheenes’ lawsuit, claiming that it was “impossible to produce material witnesses because of death.” The suit went nowhere.

In 1950, Sheene, Jr.,’s mother, Alice, took Sheene, Sr., to court. The two had long been separated, and Alice accused Sheene, Sr., of failing to provide her with financial support. On the day of his deposition, Sheene, Sr., was unemployed and living with his sister. He claimed to have only two dollars to his name. Over the years, he’d given his son a hundred and fifty thousand dollars (roughly two million dollars today), for numerous ventures. Asked in court if he expected to be paid back, Sheene, Sr., said, “You can’t get blood out of a turnip. He hasn’t got a dime.”

“How do you expect your wife to live?” Alice’s lawyer asked. There was a long silence. “Did you hear the question?”

“I am trying to think of an answer,” Sheene, Sr., said. “I don’t know.”

After the deposition, the I.R.S. went after Sheene, Sr., Sheene, Jr., and Briscoe for back taxes. (Together, they owed the modern equivalent of some three million dollars.) Unable to rely on her ex-husband or her son, Alice moved close to Biden, Sr., her nephew and godson. She rented a room in a house a couple of miles away. Jean put up with the arrangement, knowing that Alice was like a second mother to Biden, Sr. “My mother would pick her up every morning and take her to our house, where she sat on the left-hand side of the couch all day,” Valerie recalled. “Then, after dinner, my mom brought her home.” Eventually, Alice began helping Jean with household chores, ironing the white shirts that the Biden children wore to school. Joe Biden and his siblings called her Aunt Al.

For several months, Sheene, Jr., lived at the Bidens’ house in Mayfield, Valerie said. This was harder for Jean to accept. (“I wasn’t crazy about him either,” Valerie said, of Sheene, Jr.) His drinking had got worse—as Sheene III said, “He couldn’t get up in the morning and go to work without a shot.” After he moved out, he regularly returned to Mayfield to go out drinking with Biden, Sr., and, on occasion, to attend Biden family gatherings.

Toward the end of Sheene, Jr.,’s life, Biden, Sr., would visit him in Maryland. “My father would basically go down and minister to him, to let him know that he’s not alone in the world,” Frank said. In the spring of 1969, Biden, Sr., Sheene, Jr., and Sheene III spent the day fishing on the Chesapeake. Sheene III said that his father told him that Biden would be joining them. But Biden—whose wife, Neilia, had recently given birth to their first son—didn’t show up, Sheene III said, so the men set off without him.

Sheene, Jr.,’s doctor had told him that if he didn’t cut back on his drinking he would die. But the warning didn’t stop him that day. Sheene III remembered his father polishing off two or three bottles of wine by himself. When they ran out of wine, they switched to beer, and when they were done fishing Sheene, Jr., took them to a bar in Annapolis, where the men drank whiskey deep into the night. “Joe kept saying to him, ‘Slow down, Bill, slow down,’ ” Sheene III recalled. It was the last time that Sheene III saw his father alive. That April, at the age of fifty-four, Sheene, Jr., died, of cirrhosis of the liver. He was buried in Loudon Park Cemetery, a few feet from Joseph Harry and Mary Biden.