How Britain won the battle for the Falklands

An English ship made the first recorded landing on the islands, an uninhabited archipelago about 300 miles from the South American coast, in 1690, naming them after the expedition’s sponsor, Viscount Falkland. The French, however, established the first settlement there, in 1764: they called them the Îles Malouines after the port they’d sailed from, Saint-Malo. (Hence “Las Islas Malvinas” in Spanish.)

The British founded a rival settlement one year later, and thereafter, the islands’ status has always been contested. France ceded its claim to the Spanish empire; Britain and Spain nearly went to war over the issue in 1770, but reached an inconclusive compromise. In the early 19th century, newly independent Argentina claimed the islands.

But a row over seal-hunting led the Royal Navy to recapture the Falklands in 1833, founding a colony there in 1840. Apart from two months in 1982, the islands have been a British possession ever since.

How significant were they to the British empire?

Not very. At the time of the 1770 crisis, Dr Johnson said it was absurd to go to war over such “a bleak and gloomy solitude”. From the 1840s until the Falklands War, sheep farming was the only profitable activity. From the late 1960s, British governments resented the expense of owning them, and saw them as a barrier to good relations with South America; efforts were made to reach a deal. “Unless sovereignty is seriously negotiated and ceded,” a Foreign Office minister wrote in 1968, “in the long term we are likely to end up in a state of armed conflict with Argentina.”

There was talk of a “Hong Kong solution”: ceding the islands to Argentina and leasing them back. However, Parliament gave the islanders an effective veto, and its 1,800 inhabitants, mostly descended from Scottish and Welsh settlers, wanted to remain British. On 2 April 1982, an Argentinian military government, led by Leopoldo Galtieri, put a stop to talks when it invaded.

Why did Argentina invade?

Argentina’s right-wing dictatorship, in power since 1976, was being shaken by civil unrest and an economic crisis; a patriotic victory would be a useful distraction. The Falklands/Malvinas was one issue on which most Argentines agreed, and it was a long-standing obsession of Admiral Jorge Anaya, who had drawn up the invasion plan while still a junior naval officer.

In General Galtieri’s view, Margaret Thatcher’s government would be unlikely to engage in a distant war: “that woman wouldn’t dare”, he said. The Argentinians also thought that they could rely on a certain amount of international sympathy, in an age of widespread decolonisation.

Was there support for Argentina?

Not nearly as much as it had expected. The principle of self-determination for the islanders partially neutralised the anti-colonial argument. And even countries that rejected Britain’s claim on the islands conceded the point that international disputes shouldn’t be settled by force. It didn’t help that the aggressor was a dictatorship notorious for human rights abuses.

Britain won the day at the UN. In the meantime, with the full support of Michael Foot’s Labour Party, Margaret Thatcher hastily assembled a task force of 127 ships and 30,000 men, which would be sent 8,000 miles to the South Atlantic to retake the islands – a task the US navy had assessed as “a military impossibility”. The official historian of the campaign, Lawrence Freedman, described it as “an enormous gamble”.

How did Britain win?

It nearly didn’t: the task force was within range of Argentina’s air force, and seven ships were lost to its Exocet missiles and bombs, causing many casualties. The task force’s crucial landing at San Carlos, it is often said, could have gone very differently; many Argentinian bombs hit British ships but failed to detonate. Lord Craig, an RAF air marshal, is said to have declared: “Six better fuses and we would have lost.”

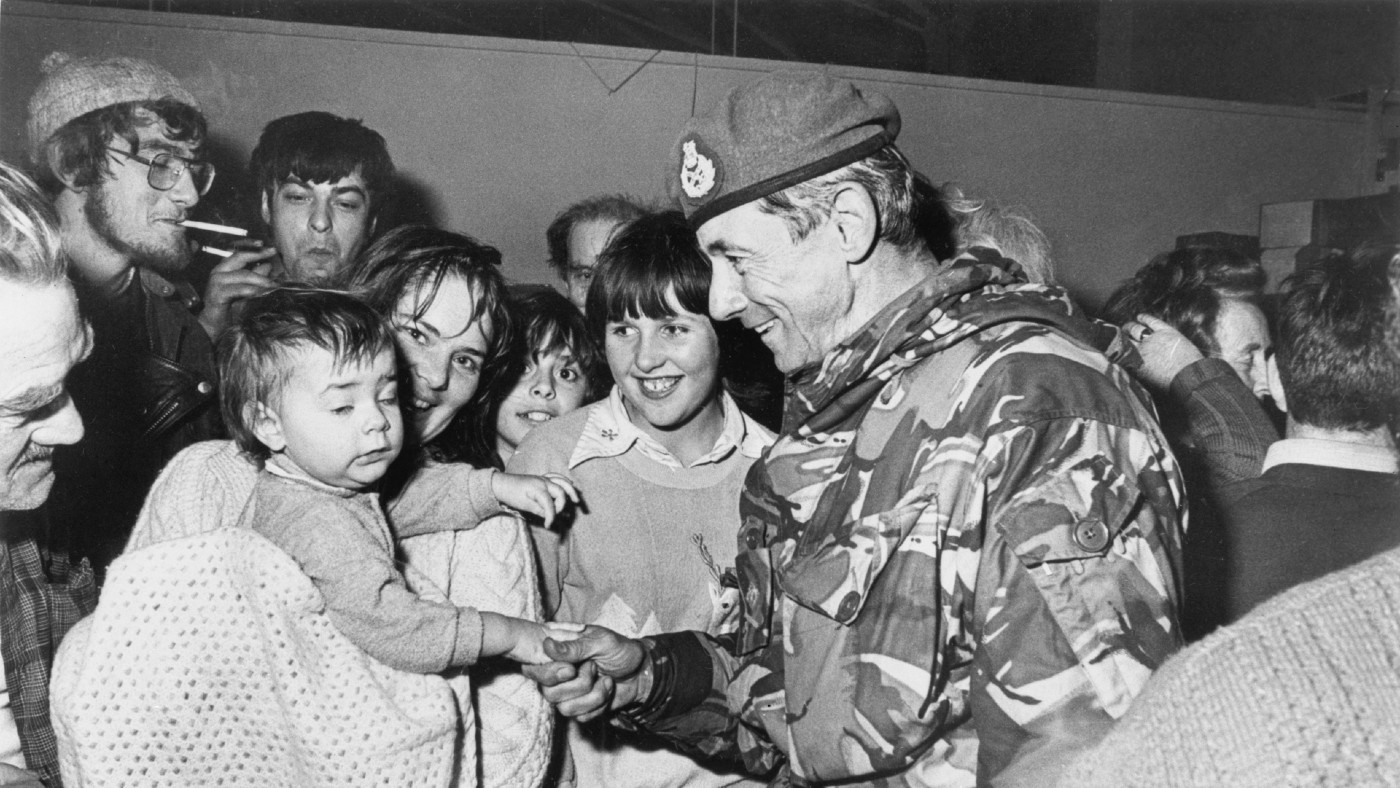

As it was, though, the 74-day campaign was a triumph for Britain. It generated some of the most iconic moments of the early Thatcher years: the PM declaring “Rejoice!” after the recapture of South Georgia; the sinking of the Belgrano; the fierce firefight at Goose Green; marines “yomping” to Port Stanley. A total of 258 British and 649 Argentinian lives were lost; 11,000 Argentinians were captured.

What political effects did it have?

The task force returned to Portsmouth in glory, and Thatcher rode a wave of nationalistic fervour to a landslide re-election victory in 1983. Many Conservatives believe that the war initiated a reverse of Britain’s postwar decline. Thatcher was forthright in linking the conflict to her domestic aims. She told the Tory backbench 1922 Committee that, after defeating the “enemy without”, she would take on the “enemy within”: the unions.

In Argentina, the defeat shattered the junta’s claim to represent the nation, and paved the way for the first free election in a decade. Even so, sceptics in both nations regarded the conflict as slightly absurd: the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges described the conflict as “a fight between two bald men over a comb”.

Is it all settled, 40 years on?

Far from it. Argentina never dropped its claim. Since 1994, the Argentinian constitution has made sovereignty over the Falklands a “permanent and irrevocable objective”. A poll last year suggests that 81% of Argentine voters support that.

The Falkland Islands are still a British Overseas Territory, and the UK insists that the wishes of the islanders remain the crucial principle; in 2013, 99.8% of them voted to remain British in a referendum. The islands are self-governing, and thanks to increased investment and the sale of fishing licences, are now relatively rich; they are defended by a garrison of 1,200 military personnel, which costs the UK about £60m annually.