Can Blacks and Jews re-boot their relationship?

You want a nice weekend getaway?

Try St. Augustine, Florida. It is the oldest city in North America, a beautiful small city of narrow streets, shops, restaurants, and beaches.

And, as you would expect, history.

Call this the tale of three monuments.

Take a waterfront stroll with me down Avenida Menendez Street.

The first monument commemorates the place where Ponce De Leon originally landed, in his quest to find the Fountain of Youth.

The second monument is only a few steps away. It marks the slave market.

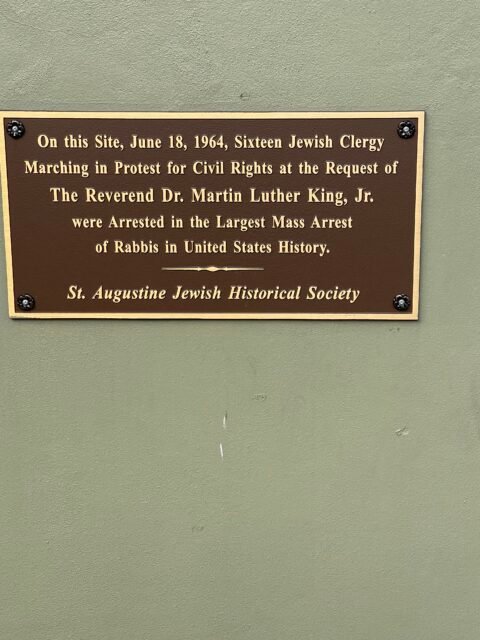

The third monument is a few more steps away. It is at the Hilton Hotel.

Back in the early 1960s, the Hilton Hotel had been the Monson Motor Lodge, and it was the site of one of the most important moments in the history of the civil rights movement, and of American Jewish history — the St. Augustine protest.

The St. Augustine protest was a delegation of sixteen Reform rabbis: Eugene Borowitz, Balfour Brickner, Israel “Sy” Dresner, Daniel Fogel, Jerrold Goldstein, Joel Goor, Joseph Herzog, Norman Hirsch, Leon Jick, Richard Levy, Eugene Lipman, Michael Robinson, B.T. Rubenstein, Murray Saltzman, Allen Secher, and Clyde T. Sills — almost all of them of blessed memory.

There was one lay leader, as well — the legendary Albert Vorspan, who for decades was the director of the Social Action Commission of the Reform movement, and who served as the moral voice of our movement.

In 1964, St. Augustine was one of the most segregated cities in America. Dr. King and other activists tried to integrate a restaurant at the hotel, which led to their arrest and spending the night of June 11 in jail.

This coincided with the annual convention of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. Rev. Dr. King sent a message to the convention, inviting my colleagues to join him in St. Augustine. They accepted the invitation.

Rabbi Samuel Soskin, chairman of CCAR’s Committee on Justice and Peace, interrupted the proceedings to announce that a group of colleagues was about to make the trip to St. Augustine. “I will remind you that these men are going down with full knowledge that, perhaps, there may be violence, and … ken ger harget varen.”

In Yiddish: “They could be killed.”

In fact, they could have been. The rabbis had marched from the site of the slave market to the hotel, to the cries of white racists.

“We don’t need you n*****-lovers!” “You’re a bunch of communists!” Many held baseball bats, broken bottles, and bricks.

My late teacher, colleague, and former congregant, the great American theologian and activist, Eugene Borowitz, penned these words in the jail cell in St. Augustine:

We came because we could not stand silently by our brother’s blood. We had done that too many times before. We have been vocal in our exhortation of others, but the idleness of our hands too often revealed an inner silence; silence at a time when silence has become the unpardonable sin of our time. We came in the hope that the God of us all would accept our small involvement as partial atonement for the many things we wish we had done before and often. We came as Jews who remember the millions of faceless people, who stood quietly, watching the smoke rise from Hitler’s crematoria. We came because we know that, second only to silence, the greatest danger to man is loss of faith in man’s capacity to act.

Two days after the events in St. Augustine, in Philadelphia, Mississippi, members of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists kidnapped and killed three civil rights workers. You know those names: James Chaney, a Black man; and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two young Jews from New York. Their bodies were found in a hollow grave.

Several weeks later, the late Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld of Cleveland, Ohio, marched in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and racist hooligans beat him with a metal bar.

On the opening day of religious school in the fall, when I was in fifth grade, our teacher held up that photograph and said to us: “Boys and girls, this is a Jewish hero.”

I have long forgotten most of the things that happened to me during my religious school years, but this occurrence will live within me forever.

Let us leave the Freedom Summer of 1964.

Let me bring you back to 1957 and 1958.

Many have heard of The Temple bombing — in the wee hours of October 12, 1958, when a bomb equal to fifty sticks of dynamite tore apart The Temple in Atlanta.

But, what we do not know, or what we have forgotten, is that for the entire year prior to that, in 1957 and 1958:

- November, 1957: Eleven sticks of dynamite were found at Temple Israel in Charlotte, North Carolina.

- February, 1958: Un-detonated dynamite sticks were found at Temple Emanuel in Gastonia, North Carolina.

- March, 1958: Temple Beth El in Miami was bombed.

- March, 1958: on the same day, the Nashville Jewish Center was bombed.

- April, 1958: The Jacksonville Jewish Center was blown up.

- April, 1958: Dynamite with a burnt-out fuse was found at Temple Beth-El in Birmingham, Alabama.

In the words of the historian Jonathan Sarna: “Ten percent of the bombs planted by extremists between 1954 and 1959 targeted Jewish institutions, synagogues, rabbis’ homes, and community centers.”

Some years later, in 1967, Southern racists bombed Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, Mississippi, and then two months later, the same people bombed the home of its rabbi, Perry Nussbaum.

I tell these stories, not to induce moral nostalgia, and not to present them that we might gain a new kind of “street cred” in the history of civil rights in this country.

I tell these stories, because you simply cannot tell the story of the civil rights movement without also telling a Jewish story — and in particular, a Reform Jewish story.

Because, sometimes we forget, and sometimes we need to remember.

We Jews use stories — not just to tell them, but to inspire action. The Yiddish word for “story” is mayseh, and the Hebrew word is maaseh, which means to do something.

What could these stories do?

They could reboot the relationship between Blacks and Jews, with the realization that those who hate one of us will hate both of us.

Our communities need a deep conversation about the scourge of The Great Replacement Theory — the twisted fantasy that American Jews are conspiring to bring dark-skinned immigrants into this country, precisely so that we can destroy this thing called white America. This is the theory that drove the thugs to the streets in Charlottesville, with their chants of: “The Jews will not replace us!”

It is a conspiracy theory that has become increasingly popular. Fox News host Tucker Carlson has made this theory part of his media arsenal; he has parroted the theory in more than four hundred episodes of his show. So have Republican politicians. As many as one third of all Americans believe it.

American Blacks and American Jews need to talk about this. It is not that bigotry loves company. It is that the bigotry that faces both communities must breed a new sense of solidarity, what Dr. King himself called the beloved community.

Some years ago, the late writer, Julius Lester, who taught at Smith College in Massachusetts, and who served as the cantorial soloist in his Conservative synagogue, and who happened to be a Black Jew, said these words.

“I must learn to carry my suffering as if it were a long-stemmed rose that I offer to humanity. I do that by living with my suffering so intimately so as to never do something that will intensify the existence of evil in the universe.”

He was right.

Back to that hotel parking lot in St. Augustine.

When I began to inquire about the spot of the protest, the hotel clerk interrupted me, even before I could finish my question. “Of course,” she said, and she took us out to the parking lot, and she showed us the plaque.

Proudly.

Obviously, we were walking in the footsteps of many people, over the years, who had wanted to see that spot.

Call them pilgrims to a sacred site.

For that is what it is.